During the Pueblo Revolt Which of the Following Names Were Ordered to Never Be Spoken Again

| Pueblo Defection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Spanish colonization of the Americas | |||||||

Priest killed by rebels at the mission San Miguel de Oraibi | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | Puebloans

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| | Popé meet list beneath for others | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 400, including civilians | over 600 | ||||||

The Pueblo Defection of 1680, likewise known as Popé's Rebellion or Popay'south Rebellion, was an uprising of most of the indigenous Pueblo people against the Spanish colonizers in the province of Santa Iron de Nuevo México, larger than present-day New Mexico.[1] The Pueblo Revolt killed 400 Spaniards and drove the remaining 2,000 settlers out of the province. The Spaniards reconquered New Mexico twelve years later.[ii]

Groundwork [edit]

For more 100 years commencement in 1540, the Pueblo people of present-twenty-four hours New United mexican states were subjected to successive waves of soldiers, missionaries, and settlers. These encounters, referred to as entradas (incursions), were characterized by violent confrontations betwixt Spanish colonists and Pueblo peoples. The Tiguex War, fought in the winter of 1540–41 by the expedition of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado against the twelve or thirteen pueblos of Tiwa Native Americans, was particularly subversive to Pueblo and Spanish relations.

In 1598 Juan de Oñate led 129 soldiers and 10 Franciscan priests, plus a large number of women, children, servants, slaves, and livestock, into the Rio Grande valley of New Mexico. There were at the time approximately 40,000 Pueblo Native Americans inhabiting the region. Oñate put downwards a revolt at Acoma Pueblo by killing and enslaving hundreds of the Native Americans and sentencing all men 25 or older to have their foot cut off. The Acoma Massacre would instill fright of and anger at the Castilian in the region for years to come, though Franciscan missionaries were assigned to several of the Pueblo towns to Christianize the natives.[3]

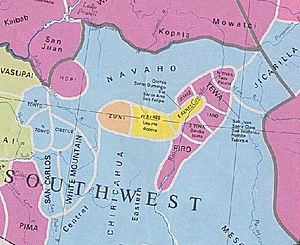

The location of the Pueblo villages and their neighbors in early on New United mexican states.

Spanish colonial policies in the 1500s regarding the humane treatment of native citizens were often ignored on the northern frontier. With the establishment of the beginning permanent colonial settlement in 1598, the Pueblos were forced to provide tribute to the colonists in the form of labor, basis corn, and textiles. Encomiendas were shortly established by colonists along the Rio Grande, restricting Pueblo access to fertile farmlands and water supplies and placing a heavy brunt upon Pueblo labor.[four] Specially egregious to the Pueblo was the assault on their traditional organized religion. Franciscan priests established theocracies in many of the Pueblo villages. In 1608, when it looked as though Spain might abandon the province, the Franciscans baptized seven thousand Pueblos to try to convince the Crown otherwise.[5] Although the Franciscans initially tolerated manifestations of the old organized religion as long as the Puebloans attended mass and maintained a public veneer of Catholicism, Fray Alonso de Posada (in New Mexico 1656–1665) outlawed Kachina dances by the Pueblo people and ordered the missionaries to seize and burn their masks, prayer sticks, and effigies.[6] The Franciscan missionaries also forbade the employ of entheogenic substances in the traditional religious ceremonies of the Pueblo. Several Spanish officials, such as Nicolas de Aguilar, who attempted to curb the power of the Franciscans were charged with heresy and tried earlier the Inquisition.[ further explanation needed ]

In the 1670s drought swept the region, causing a famine among the Pueblo and increased raids by the Apache, which Spanish and Pueblo soldiers were unable to prevent. Fray Alonso de Benavides wrote multiple letters to the King, describing the conditions, noting "the Spanish inhabitants and Indians akin to eat hides and straps of carts".[vii] The unrest amongst the Pueblos came to a caput in 1675. Governor Juan Francisco Treviño ordered the abort of forty-vii Pueblo medicine men and accused them of practicing "sorcery".[eight] Four medicine men were sentenced to decease past hanging; three of those sentences were carried out, while the fourth prisoner committed suicide. The remaining men were publicly whipped and sentenced to prison. When this news reached the Pueblo leaders, they moved in strength to Santa Iron, where the prisoners were held. Because a big number of Castilian soldiers were away fighting the Apache, Governor Treviño was forced to accede to the Pueblo demand for the release of the prisoners. Amidst those released was a San Juan ("Ohkay Owingeh" in the Tewa Language) native named "Popé".[viii]

Rebellion [edit]

Taos Pueblo served as a base of operations for Popé during the revolt.

Following his release, Popé, forth with a number of other Pueblo leaders (see list below), planned and orchestrated the Pueblo Revolt. Popé took up residence in Taos Pueblo far from the capital of Santa Fe and spent the next five years seeking support for a defection amidst the 46 Pueblo towns. He gained the back up of the Northern Tiwa, Tewa, Towa, Tano, and Keres-speaking Pueblos of the Rio Grande Valley. The Pecos Pueblo, 50 miles e of the Rio Grande pledged its participation in the revolt every bit did the Zuni and Hopi, 120 and 200 miles respectively west of the Rio Grande. The Pueblos not joining the revolt were the four southern Tiwa (Tiguex) towns most Santa Fe and the Piro Pueblos south of the principal Pueblo population centers virtually the present solar day city of Socorro. The southern Tiwa and the Piro were more thoroughly integrated into Castilian culture than the other groups.[9] The Spanish population of about 2,400, including mixed-claret mestizos, and native servants and retainers, was scattered thinly throughout the region. Santa Fe was the just identify that approximated existence a town. The Castilian could only muster 170 men with arms.[x] The Pueblos joining the revolt probably had two,000 or more adult men capable of using native weapons such as the bow and arrow.[11] Information technology is possible that some Apache and Navajo participated in the defection.

Pueblo runner carries a knotted cord to Hopi villages. Each knot represents a day to countdown until the kickoff of the Pueblo Rebellion.

The Pueblo revolt was typical of millenarian movements in colonial societies. Popé promised that, once the Castilian were killed or expelled, the ancient Pueblo gods would advantage them with health and prosperity.[9] Popé's plan was that the inhabitants of each Pueblo would ascension upward and kill the Spanish in their area and so all would advance on Santa Atomic number 26 to kill or expel all the remaining Spanish. The appointment set for the uprising was August 11, 1680. Popé dispatched runners to all the Pueblos carrying knotted cords.

Each morning the Pueblo leadership was to untie ane knot from the cord, and when the final knot was untied, that would exist the signal for them to rise confronting the Spaniards in unison. On August 9, however, the Spaniards were warned of the impending revolt by southern Tiwa leaders and they captured two Tesuque Pueblo youths entrusted with conveying the message to the pueblos. They were tortured to make them reveal the significance of the knotted cord.[12]

Popé then ordered the defection to begin a day early on. The Hopi pueblos located on the remote Hopi Mesas of Arizona did not receive the avant-garde notice for the beginning of the defection and followed the schedule for the revolt.[xiii] On August 10, the Puebloans rose upwards, stole the Spaniards' horses to prevent them from fleeing, sealed off roads leading to Santa Fe, and pillaged Spanish settlements. A full of 400 people were killed, including men, women, children, and 21 of the 33 Franciscan missionaries in New United mexican states.[14] [xv] In the rebellion at Tusayan (Hopi) churches at Awatovi, Shungopavi, and Oraibi were destroyed and the attending priests were killed.[16] Survivors fled to Santa Fe and Isleta Pueblo, 10 miles south of Albuquerque and one of the Pueblos that did not participate in the rebellion. By Baronial 13, all the Castilian settlements in New United mexican states had been destroyed and Santa Fe was besieged. The Puebloans surrounded the city and cut off its water supply. In desperation, on August 21, New Mexico Governor Antonio de Otermín, barricaded in the Palace of the Governors, sallied outside the palace with all of his available men and forced the Puebloans to retreat with heavy losses. He then led the Spaniards out of the metropolis and retreated southward forth the Rio Grande, headed for El Paso del Norte. The Puebloans shadowed the Spaniards only did not attack. The Spaniards who had taken refuge in Isleta had besides retreated southward on Baronial 15, and on September vi the two groups of survivors, numbering 1,946, met at Socorro. About 500 of the survivors were Native American slaves. They were escorted to El Paso by a Castilian supply train. The Puebloans did not block their passage out of New United mexican states.[17] [18]

Popé'southward country [edit]

The retreat of the Spaniards left New Mexico in the power of the Puebloans.[xix] Popé was a mysterious effigy in the history of the southwest every bit in that location are many tales among the Puebloans of what happened to him subsequently the defection. Later testimony to the Spanish past the Pueblo people was probably colored by anti-Popé sentiments and a desire to tell the Castilian what they wanted to hear.

Patently, Popé and his two lieutenants, Alonso Catiti from Santo Domingo and Luis Tupatu from Picuris, traveled from town to town ordering a render "to the land of their antiquity." All crosses, churches, and Christian images were to exist destroyed. The people were ordered to cleanse themselves in ritual baths, to employ their Puebloan names, and to destroy all vestiges of the Roman Cosmic religion and Spanish culture, including Spanish livestock and fruit copse. Popé, it was said, forbade the planting of wheat and barley and allowable those natives who had been married co-ordinate to the rites of the Catholic Church to dismiss their wives and to accept others after the quondam native tradition.[twenty]

The Puebloans had no tradition of political unity. Popé was a man of trust and strict policy. Therefore, each pueblo was self-governing, and some, or all, plainly resisted Popé'due south demands for a return to a pre-Spanish existence. The paradise Popé had promised when the Spanish were expelled did not materialize. A drought continued, destroying Puebloan crops, and the raids by Apache and Navajo increased. Initially, however, the Puebloans were united in their objective of preventing a return of the Castilian.[21]

Popé was deposed as the leader of the Puebloans about a twelvemonth after the revolt and disappears from history.[22] He is believed to have died shortly earlier the Spanish reconquest in 1692.[23]

Spanish endeavor to return [edit]

In Nov 1681, Antonio de Otermin attempted to return to New United mexican states. He assembled a strength of 146 Castilian and an equal number of native soldiers in El Paso and marched north along the Rio Grande. He kickoff encountered the Piro pueblos, which had been abased and their churches destroyed. At Isleta pueblo he fought a brief battle with the inhabitants and then accepted their surrender. Staying in Isleta, he dispatched a company of soldiers and natives to establish Spanish authority. The Puebloans feigned surrender while gathering a large strength to oppose Otermin. With the threat of a Puebloan attack growing, on January 1, 1682 Otermin decided to return to El Paso, burning pueblos and taking the people of Isleta with him. The first Spanish endeavour to regain command of New Mexico had failed.[18]

Some of the Isleta later returned to New United mexican states, but others remained in El Paso, living in the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo. The Piro also moved to El Paso to live amidst the Spaniards, somewhen forming part of the Piro, Manso, and Tiwa tribe.[24]

The Spanish were never able to re-convince some Puebloans to join Santa Fe de Nuevo México, and the Spanish frequently returned seeking peace instead of reconquest. For instance, the Hopi remained costless of any Spanish attempt at reconquest; though they did, at several not-violent attempts, effort for unsuccessful peace treaties and unsuccessful trade agreements.[25] For some Puebloans, the Defection was a success in its objective to bulldoze away Castilian influence.

Reconquest [edit]

The Spanish return to New United mexican states was prompted past their fears of French advances into the Mississippi valley and their desire to create a defensive frontier against the increasingly aggressive nomadic tribes on their northern borders.[26] [27] In August 1692, Diego de Vargas marched to Santa Fe unopposed forth with a converted Zia war captain, Bartolomé de Ojeda. De Vargas, with just sixty soldiers, one hundred Indian auxiliaries or native soldiers, seven cannons (which he used as leverage against the Pueblo inside Santa Fe), and one Franciscan priest, arrived at Santa Iron on September 13. He promised the 1,000 Pueblo people assembled at that place clemency and protection if they would swear allegiance to the King of Spain and render to the Christian organized religion. Afterward a while the Pueblo rejected the Spaniards. Later on much persuading, the Spanish finally made the Pueblo concord to peace. On September fourteen, 1692,[28] de Vargas proclaimed a formal act of repossession. It was the thirteenth town he had reconquered for God and Male monarch in this manner, he wrote jubilantly to the Conde de Galve, viceroy of New Spain.[28] During the next month de Vargas visited other Pueblos and accepted their acquiescence to Spanish rule.

Though the 1692 agreement to peace was bloodless, in the years that followed de Vargas maintained increasingly severe control over the increasingly defiant Pueblo. De Vargas returned to Mexico and gathered together about 800 people, including 100 soldiers, and returned to Santa Atomic number 26 on December 16, 1693. [29] This time, nonetheless, 70 Pueblo warriors and 400 family unit members inside the town opposed his entry. De Vargas and his forces staged a quick and encarmine recapture that concluded with the surrender and execution of the 70 Pueblo warriors on December thirty, and their surviving families (virtually 400 women and children) were sentenced to x years' servitude and distributed to the Castilian colonists as slaves.[30] [31]

In 1696 the residents of 14 pueblos attempted a second organized revolt, launched with the murders of five missionaries and thirty-four settlers and using weapons the Spanish themselves had traded to the natives over the years; de Vargas's retribution was unmerciful, thorough and prolonged.[30] [32] By the end of the century the last resisting Pueblo boondocks had surrendered and the Spanish reconquest was essentially complete. Many of the Pueblos, withal, fled New Mexico to bring together the Apache or Navajo or to attempt to re-settle on the Smashing Plains.[26] One of their settlements has been found in Kansas at El Cuartelejo.[33]

While the independence of many pueblos from the Spaniards was short-lived, the Pueblo Revolt gained the Pueblo people a measure of freedom from future Spanish efforts to eradicate their culture and organized religion post-obit the reconquest. Moreover, the Castilian issued substantial country grants to each Pueblo and appointed a public defender to protect the rights of the Native Americans and fence their legal cases in the Castilian courts. The Franciscan priests returning to New Mexico did non again endeavour to impose a theocracy on the Pueblo who continued to practice their traditional faith.[27]

In the arts [edit]

The 1994 Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Journey's End" references the Pueblo Revolt, in the context of ancestors of different characters having been involved in the revolt.[34]

In 1995, in Albuquerque, La Compañía de Teatro de Albuquerque produced the bilingual play Casi Hermanos, written by Ramon Flores and James Lujan. It depicted events leading upward to the Pueblo Revolt, inspired by accounts of two half-brothers who met on opposite sides of the battlefield.[ citation needed ]

A statue of Po'Pay by sculptor Cliff Fragua was added to the National Statuary Hall Collection in the US Capitol Building in 2005 as one of New United mexican states's two statues.[35]

In 2005, in Los Angeles, Native Voices at the Autry produced Kino and Teresa, an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet written by Taos Pueblo playwright James Lujan. Set five years after the Spanish Reconquest of 1692, the play links actual historical figures with their literary counterparts to dramatize how both sides learned to live together and form the culture that is present-day New Mexico.[ commendation needed ]

In 2010, students Clara Natonabah, Nolan Eskeets, Ariel Antone, members of the Santa Fe Indian School Spoken Give-and-take Team wrote and performed their spoken word slice telling the story of the Pueblo Revolt, "Po'pay" to critical acclaim in New Mexico and the US. The team performed in the Baltic states of Republic of estonia, Republic of latvia, and Republic of lithuania. The track tin can be found on iTunes.[ citation needed ]

Pueblo defection leaders and their dwelling pueblos [edit]

- Ku-htihth (Cochiti): Antonio Malacate

- Galisteo (Galisteo): Juan El Tano

- Walatowa (Jemez): Luis Conixu

- Nambé (Nambé): Diego Xenome

- Welai (Picuris): Luis Tupatu (Ciervo Blanco)

- Powhogeh (San Ildefonso): Francisco El Ollito and Nicolas de la Cruz Jonv

- Ohkay (San Juan): Po'pay and Tagu

- San Lazaro: Antonio Bolsas and Cristobal Yope

- Khapo (Santa Clara): Domingo Naranjo and Cajete

- Kewa (Santo Domingo): Alonzo Catiti

- Teotho (Taos): El Saca

- Tehsugeh (Tesuque): Domingo Romero [36]

Come across too [edit]

- List of battles fought in New Mexico

- List of conflicts in the United States

- Spanish missions in New Mexico

- Fiestas de Santa Fe

- Zozobra

- California mission clash of cultures

- Astialakwa

References [edit]

- ^ David Throughway (November 2003). Roadside New Mexico (August 15, 2004 ed.). University of New Mexico Printing. p. 189. ISBN0-8263-3118-1.

- ^ The Pueblo Revolt of 1680:Conquest and Resistance in Seventeenth-Century New Mexico, By, Andrew L. Knaut, University of Oklahoma Printing: Norman, 1995

- ^ Riley, Carroll Fifty. Rio del Norte: People of the Upper Rio Grande from Earliest Times to the Pueblo Revolt Salt Lake City: U of UT Printing, 1995, pp. 247–251

- ^ Wilcox, Michael V., "The Pueblo Defection and the Mythology of conquest: an Indigenous archaeology of contact", University of California Press, 2009

- ^ Forbes, Jack D., "Apache, Navaho, and Spaniard", Oklahoma, 1960 pp. 112

- ^ Sando, Joe S., Pueblo Nations: Eight Centuries of Pueblo Indian History, Clear Light Publishers, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1992 pp. 61–62

- ^ Hackett, Charles Wilson. Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizacaya and Approaches Thereto in 1773, 3 vols, Washington, 1937

- ^ a b Sando, Joe Southward., Pueblo Nations: Eight Centuries of Pueblo Indian History, Clear Light Publishers, Santa Atomic number 26, New United mexican states, 1992 p. 63

- ^ a b Riley, p. 267

- ^ John, Elizabeth A. H. Storms Brewed in Other Men'south Worlds Lincoln: U of NE Press, 1975, p. 96

- ^ "The Peublo Revolt: The Pueblo Indians in the province of New Mexico had long chafed under Castilian dominion. In 1680 all their grievances flared into a violent rebellion that surprised the Europeans with its ferocity - Document - Gale OneFile: Pop Magazines". get.gale.com . Retrieved 2021-x-17 .

- ^ Gutierrez, Ramon A. When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away Stanford: Stanford U Press, 1991, p. 132

- ^ Pecina, Ron and Pecina, Bob. Neil David'southward Hopi Earth. Schiffer Publishing 2011. ISBN 978-0-7643-3808-3. pp. xiv–15.

- ^ "The Peublo Defection: The Pueblo Indians in the province of New Mexico had long chafed under Spanish rule. In 1680 all their grievances flared into a violent rebellion that surprised the Europeans with its ferocity - Certificate - Gale OneFile: Pop Magazines". become.gale.com . Retrieved 2021-10-17 .

- ^ Liebmann, Matthew (2012). Revolt : an archaeological history of Pueblo resistance and revitalization in 17th century New Mexico. Tucson: Academy of Arizona Printing. ISBN978-0-8165-9965-iii. OCLC 828490601.

- ^ Pecina, Ron and Pecina, Bob. Neil David's Hopi World. Schiffer Publishing 2011. ISBN 978-0-7643-3808-3. pp. 16-17.

- ^ Gutierrez, pp 133–135

- ^ a b Flint, Richard and Shirley Cushing. "Antonio de Otermin and the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 [ permanent dead link ] ." New Mexico Part of the State Historian, accessed 29 Oct 2013.

- ^ Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flintstone (2009). "Bartolome de Ojeda". New United mexican states Role of the State Historian. Archived from the original on September eighteen, 2009. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- ^ Gutierrez, p. 136

- ^ John, pp. 106–108

- ^ Gutierrez, p. 139

- ^ Popé, Public Broadcasting Organisation, accessed 25 Jul 2012

- ^ Campbell, Howard. "Tribal synthesis: Piros, Mansos, and Tiwas through history." Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. 12, 2006. 310–302

- ^ James, H.C. (1974). Pages from Hopi History . University of Arizona Press. p. 61. ISBN978-0-8165-0500-5 . Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ a b Flint, Richard and Shirley Cushing, "de Vargas, Diego Archived 2012-03-24 at the Wayback Machine." New Mexico Office of the State Historian, accessed 29 Jul 2012

- ^ a b Gutierrez, p. 146

- ^ a b Kessell, John L., 1979. Kiva, Cross & Crown: The Pecos Indians and New Mexico, 1540–1840. National Park Service, U.Southward. Department of the Interior: Washington, DC.

- ^ Robert West. Preucel, Archaeologies of the Pueblo Defection: Identity, Meaning, and Renewal in the Pueblo Earth (University of New Mexico Press, 2007) p. 207

- ^ a b Kessell, John 50., Rick Hendricks, and Meredith D. Dodge (eds.), 1995. To the Majestic Crown Restored (The Journals of Don Diego De Vargas, New Mexico, 1692–94). University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque.

- ^ Ramón A. Gutiérrez, When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away: Spousal relationship, Sexuality, and Ability in New Mexico, 1500-1846 (Stanford University Press, 1991) p. 145

- ^ Kessell, John L., Rick Hendricks, and Meredith D. Dodge (eds.), 1998. Blood on the Boulders (The Journals of Don Diego De Vargas, New Mexico, 1694–97). University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque.

- ^ "El Cuartalejo Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Motorcar" National Park Service

- ^ "The Next Generation Transcripts - Journeying'due south End-". Chrissie's Transcripts Site . Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ Sando, Joe Due south. and Herman Agoyo, with contributions by Theodore Due south. Jojola, Robert Mirabal, Alfoonso Ortiz, Simon J. Ortiz and Joseph H. Suina, foreword by Neb Richardson, Po'Pay: Leader of the First American Revolution, Clear Lite Publishing, Santa Iron, New Mexico, 2005

- ^ Sando, Joe Southward. and Herman Agoyo, editors, Po'pay: Leader of the First American Revolution, Clear Light Publishing, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2005 p. 110

Bibliography [edit]

- Espinosa, J. Manuel. The Pueblo Indian defection of 1696 and the Franciscan missions in New United mexican states: messages of the missionaries and related documents, Norman : University of Oklahoma Press, 1988.

- Hackett, Charles Wilson. Defection of the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico and Otermín's Attempted Reconquest, 1680-1682, ii vols, Albuquerque: Academy of New United mexican states Printing, 1942.

- Knaut, Andrew 50. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680, Norman: University of Oklahoma Printing, 1995. 14.

- Liebmann, Matthew. Revolt: An Archaeological History of Pueblo Resistance and Revitilization in 17th Century New United mexican states, Tucson: Academy of Arizona Printing, 2012.

- Ponce, Pedro, "Problem for the Castilian, the Pueblo Revolt of 1680", Humanities, November/December 2002, Volume 23/Number half-dozen.

- PBS The West – Events from 1650 to 1800

- Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 448. ISBN978-0544602670.

- Salpointe, Jean Baptiste, Soldiers of the Cross; Notes on the Ecclesiastical History of New-Mexico, Arizona and Colorado, Salisbury, N.C.: Documentary Publications, 1977 (reprint from 1898).

- Simmons, Marker, New Mexico: An Interpretive History, Albuquerque: Academy of New Mexico Press, 1977.

- Weber, David J. ed., What Caused the Pueblo Defection of 1680? New York: Bedford/St. Martin's Printing, 1999.

- Preucel, Robert Due west., 2002. Archaeologies of the Pueblo Defection: Identity, Meaning, and Renewal in the Pueblo World. University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque.

- Wilcox, Michael V., "The Pueblo Revolt and the Mythology of conquest: an Indigenous archaeology of contact", University of California Printing, 2009.

External links [edit]

- PBS Documentary almost the Pueblo Revolt: Frontera!

- ancientweb.org/America

- PBS: The W – Archives of the Due west. "Alphabetic character of the governor and helm-full general, Don Antonio de Otermin, from New Mexico, in which he gives him a total account of what has happened to him since the twenty-four hours the Indians surrounded him. [September 8, 1680.]" Retrieved Nov. 2, 2009.

- Pueblo Rebellion

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pueblo_Revolt

0 Response to "During the Pueblo Revolt Which of the Following Names Were Ordered to Never Be Spoken Again"

Post a Comment